HISTORICAL PHOTOS

As well as recent scientific evidence, we can compare historical with recent photographic records to better understand the longer-term changes happening on the foreshore. Hoylake’s natural ecosystem, until its replacement over the last 150 years by sea walls, roads and houses was an extensive sand dune system which stretched along the coast from Hoylake to New Brighton.

photo courtesy Mr Mycetes [sadoldgit.com]

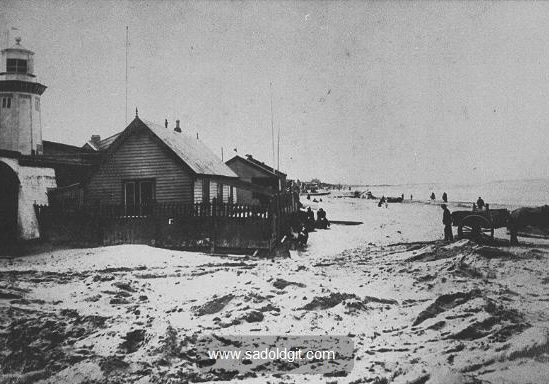

Figure 16: The Lower Lighthouse in the late 1800s. Before the promenade wall was built, what is now North Parade was sand dunes, part of an extensive system which stretched along the coast from Hoylake to New Brighton.

Figure 18: The beach level in 2019 at Old Lifeboat Station slipway. It is now risen to between between the seventh and eighth post. Now look back at the previous image. What we are looking at here is the underlying beach level, not windblown sand whose level varies depending on tide and weather conditions. As we can clearly see, the significant rise in the underlying beach level in just over 100 years is incontrovertible.

Hoylake’s natural ecosystem, until its replacement over the last 150 years by sea walls, roads and houses was an extensive sand dune system which stretched along the coast from Hoylake to New Brighton. Dunes form a natural coastal protection between the sea and the land.

We can see in the first image above how the Lower Lighthouse was built just above the highest tide line, just behind a protective line of sand dune.

The building of the promenade wall created an “amenity” beach popular with Victorians, allowing the wind and the sea to blow and wash away the remaining sand after the wall was built. We can see in the second image just how much lower the sand level adjacent to the wall became as it achieved a new equilibrium with the rest of the foreshore; what we have for decades considered to be "Hoylake beach".

But this equilibrium could only ever be temporary: ever since the wall was built, the same natural processes that created and fed that ancient dune system continued. The same ongoing siltation from the Dee, combined with an ample, and increasing, supply of dry, windblown sand will inevitably continue. We can rake and spray ad infinitum. It won't work.

Indeed, these processes have accelerated in recent years as is now clearly evident from more technologically advanced methods of monitoring including LIDAR (satellite) scanning and beach volume analyses. We now know the beach level is increasing at a rate of 30 cms per decade in parts.

photo courtesy Mr Mycetes [sadoldgit.com]

Figure 17: Lower Lighthouse and Lifeboat Station slipway, a few years after the promenade wall was built. Note where the bottom of the slipway meets the beach is out of the image. In the foreground sits a donkey; its head level with the base of the first vertical post.

Figure 19: Windblown sand builds up against the promenade wall. This will likely be washed away by winter storms and high tides, but as the underlying beach level rises, it will simply return and reach higher year on year. The result is ever-increasing amounts of windblown sand on the road and private driveways, which instead would naturally be feeding a rapidly developing dune ridge.

Historical photographs of the beach should be considered carefully and in the light of up-to-date scientific evidence.

Some old photographs show sand high up on the promenade wall in areas where windblown sand is trapped, such as in a corner adjacent to the old swimming baths or the slipways.

These serve only to demonstrate the high levels of windblown sand at Hoylake which then, as now, would naturally be feeding the dune system that was present before the wall was built. Windblown sand levels adjacent to walls are very different to the underlying beach level just a few metres away, as seen above and in many other old and more recent photographs.

It is also worth considering that the surface water outlets the Victorians built into the promenade wall would never have been built below the underlying beach level.

However, some of these are now well beneath this level. This presents a serious problem as clearing these is much more difficult than clearing the softer windblown sand as in the past; look now for thick vegetation growing around these buried outlets after they are cleared.

Natural processes do not simply stop dead as a consequence of human intervention. Over a period of more than 100 years this can have dramatic consequences, such as those we are now witnessing.